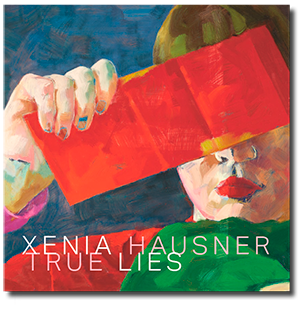

XENIA HAUSNER

TRUE LIES

Hirmer Publisher, 2020

240 pages, 120 colour illustrations

29.5 × 29.5 cm, hardcover

ISBN: 978-3-7774-3538-1 English

ISBN: 978-3-7774-3529-9 Deutsch

Ed. Klaus Albrecht Schröder, Elsy Lahner

Contributions by P. Blom, J. Crispin, S. Eiblmayr, M. Gaponenko, L. Gascoigne, A. Heller, E. Jelinek, D. Kehlmann, E. Lahner, T. Macho, E. Menasse, Ch. Ransmayr, L. Rideal, K. Sykora, B. Zemann

Text in Deutsch

Eva Menasse

This enormous energy, this desire for an immediately imminent but never visible explosion, is the glory of Hausner’s painting. Everyone notices it, but no one can explain it. The great literary historian Peter von Matt once described poems as “frozen lightning”: as linguistic and emotional distillations, they must capture forever the focused power of lightning. Are Hausner’s paintings, in analogy, frozen explosions of color and emotion? Less in linear arrow mode, and more in three-dimensional bubble mode, if anyone is still following me? That is what I think. And it can, as in mathematics, be proved by cross-checking.

The world of Xenia Hausner is populated by women with challenging gazes. If anyone is looking for feminine self-confidence—they will find it here. As I have said, the gazes of these women effectively shoot out at you from the paintings. I can find no words that fully describe them, as neither scorn nor condescension, neither flirtatiousness nor coldness nor confrontation, fully capture them. They are always a combination of all of these, perhaps best described by the multi-purpose term “challenge.” How violent is the effect when this method is altered, as in the works Blind Date (pp. 44/45) and Am Rand (On the Edge, pp. 38/39) when the gazes are obstructed or concealed!

Daniel Kehlmann

So what would life be like in a universe created not by God but by Xenia Hausner? It would be uncanny, in the original sense of the word. It would be a life you were never sure about. Not only the colors, but also the sounds and smells would be brutally intense. I imagine the air as electrically charged. And the people? They would be overwhelmingly open and at the same time entirely opaque. You would understand them, but you would not be able to trust them. None of their gestures would be unambiguous, none of their actions completely clear, but none of them would be insignificant either.

I imagine that in this world you would always feel as if you were on a stage, constantly blinking into the bright spotlight and sensing the presence of a dark auditorium with a silent, attentive audience. In Luis Buñuel’s film The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, about a group of people repeatedly defeated in their attempts to meet for dinner, the series of obstacles becoming increasingly absurd, there is an episode in which the protagonists believe they have finally succeeded. They sit down at the table, and the meal can begin—but suddenly a curtain rises, and they realize that they are part of a play. Applause breaks out. Embarrassed, indeed strangely caught out, they get to their feet and sheepishly leave the stage.

Christoph Ransmayr

2 Faye*

It was the way in which those eyes appeared to mirror a billowing sail, the river bank and the vast expanses of sluggishly passing fields, as if this woman had only to close her eyes and all reflections, objects and living things would disappear . . . Yes, that was it, that must have been it: it was as if that gaze was the origin from which every line of perspective in the visible world was derived. A person capable of opening such eyes could create whatever she saw or make it vanish.

Faye had looked at her husband from the depths of similar bright-green eyes, and, through the sheer bottomlessness of that gaze, in which the iris pigments shimmered like inclusions in the emeralds he sometimes inserted into his mechanical creatures for eyes, made him—Alister Cox, the most famous builder of automata that England had ever produced—her lover, her husband and the father of her only daughter. He ran a constant risk of ruin if she were ever to lower her eyes or avert her gaze.

In thrall? Had Alister Cox been in thrall to his wife? Faye never imposed her will on him nor wanted anything from him—in any case, none of what Cox craved, night after night and throughout the day and whenever he was with her. Faye hadn’t wanted him to kiss her or take her in his arms or rip off her clothes and bury her beneath him as a predator buries its prey . . . And she didn’t want, had never wanted him to squirm and moan on top of her until, overcome with rage, pain and disgust, she felt his seed penetrate deep inside her, strike her to the core and then crawl out of her like a shapeless, watery bug, soiling her thighs and the bed sheet.

And yet she had admired the man, in the midst of his glittering mechanical creatures, who tormented her and, as he repeatedly whispered, as if begging for forgiveness, worshipped her, and even felt for him something she could only describe as love.

*From Cox, or The Course of Time, trans. Simon Pare. Seagull Books, London/New York/Calcutta, 2020.